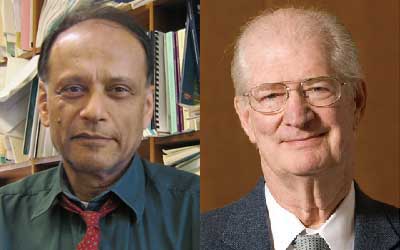

In developing this system, Sukhdev sought out the opinions of experts. He read David Pearce, a pioneer in environmental economics, and communicated with him about his ideas.

While Sukhdev at first thought that an important man like Professor Pearce would not have time for him, the professor expressed great interest in his ideas and even met with him to discuss them. Professor Pearce advised Sukhdev and introduced him to others with an interest in environmental economics. Sukhdev was only able to meet with Professor Pearce only three times before the professor passed away, but their association was of tremendous value to him in developing his ideas.

Greatly encouraged by Professor Pearce, his confidence grew to the point that he felt ready to devote himself to environmental accounting. This was in 2003, when Sukhdev was 43.